By Kamiliah Bahdar

A Non-Response:

It is common practice that artists collaborate with other artists to create ideas and art works. Increasingly, such approaches are deployed between artists andcurators. The exhibition produced out of such contexts can sometimes be regarded as art works. It is not uncommon for artists to becurators, andcuratorsto be artists. Explore the notions of a 'curatorial community'.(6 Modules)

Charting the Conceptual

Topography of an Exhibition

This essay will take on a decidedly confessional tone.

With little to no formal understanding of art, much less any deep

informal interactions with artists, I declare myself unqualified to discuss about

artists, and their collaborations with other artists, in the creation of ideas

and artworks. To attempt to do so would just be pompous. And although I am

taking what could be construed as a crash course in curating, that does not

make me a curator. Hence, I do not identify with a curatorial community – assuming

there is one – and therefore do not presume to explore the notions of it.

But of all the fine points this particular module calls on me to

discuss, having to pick one and run with, it would have to be on the

exhibition. And even then, not ‘the exhibition’ as any sort of collective noun,

but a exhibition – the one that I am currently working on with three other

participants of Curating Lab (initially, there were four). We have been in the

discussion about the upcoming exhibition for nearly three months now, and from

the very moment of pre-conception there has been a lot of meandering, much of

it through the wobbly terrains of inchoate ideas and shaky curatorial frameworks.

And with slightly just over a month to our opening night, there is a lot of

meandering still.

(I wonder how the other two groups are doing. Are they on more steady

grounds? Do they move more sure-footedly?)

Before moving this discussion along more concrete lines, let me first

sketch a brief topography of the different terrains we have been hopping through,

backtracking now and again, and then out of there, passing through a stretch of

plateau, mountains, and valleys, to find where we are now – which is a fair

distance from where we first began.

(Was it us who consciously moved through the terrain, or was it the

conceptual topography that permutated organically?)

We were exploring different systems of collecting and displaying outside

of the museum context, dwelling notably on the avid comic collector. What are his

reasons for collecting? How does he arrange his collection? Which issues are

given premier display locations and why? How are these prime issues displayed?

And from one type of collector, we moved to another. It first began with

an analogy, when the connection between the karang guni man and his habits of

collecting and displaying were made akin to that of the curator; a curator as

opposed to a collector, because the display was often for the public’s

consumption rather than personal gratification. This analogy was developed

further, with the role of artist and conservator added to the karang guni man’s

vocation. From this focus on the actor himself, we shifted to the objects

collected – the waste of modernity, the old forgotten junk left unwanted. And

it was at this point that a slight fascination with Faizal Fadil and his Study

of Three Thermos Flasks developed.

There are two main strands that connected Faizal Fadil to the figure of

the karang guni man. Study of Three Thermos Flasks is a readymade sculptural

work that first exhibited at Sculpture in Singapore, which was curated by T.K.

Sabapathy and held at the National Museum Art Gallery from 16 November to 15

December 1991. According to The Straits Times article published on 1 December

1991, Faizal Fadil bought his flasks for about five dollars each from Sungei

Road. This local Duchampian figure had trawled Sungei Road for found objects –

a location often associated with the karang guni man and the hawking of his

junk-laden wares.

And with that, the conceptual

topography shifted. The ground swelled: the crust beneath us raised by another

layer of deposited sediments, newly arrived postulations providing resources to

build steadier curatorial frameworks and strategies. Attention was now paid to

the socio-cultural landscape of Sungei Road, and we further explored it on 29

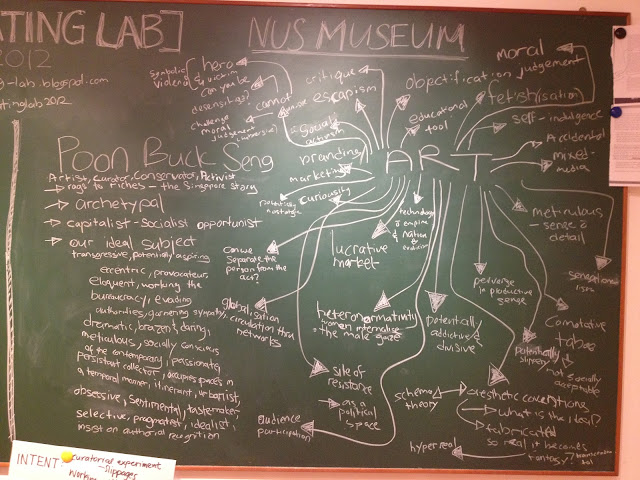

September, a hot humid sweltering Saturday. Our search for the elusive Mr Poon

Buck Seng, a karang guni personality we found on the Internet, brought us to

Sungei Road where certain held assumptions were reformed. There, we met quite

accidentally with an elderly Mr Tang – not a karang guni man (that would be

insulting), but an antique dealer. We unearthed a very different type of space in

how values of objects are negotiated. Our initial fixation on the agent as

curator transposed itself to this space – we drew parallels between Sungei Road

and the art market. Sungei Road was an alternative value economy, and for a

while, we played with the idea of colliding these two worlds in the exhibition.

Contextualising Study of Three Thermos Flasks in the present, Faizal Fadil’s

work is a disruption of both spaces. I would even posit that his is a liminal

element, an object truly straddling the in-between. The Singapore Art Museum’s

acquisition of Faizal Fadil’s Study of Three Thermos Flasks does not cement its

position as artwork. At its exhibit in Intersecting Histories: Contemporary Turns

in Southeast Asian Art, held at the ADM Gallery in September 2012, I noted that

it still elicited the comment “Is that art?” from at least one casual viewer.

Conversely, the thermos flasks remaking by the artist’s hand meant that it was

not just a pedestrian object either.

With this in mind, although possibly at the time it

was not so explicit, we thought of exploring the mechanisms of status- and

value-making by injecting disruptive elements into Sungei Road. What these

elements were, how we would go about doing it, and to what point was something

we had not quite formulated so precisely.

And we never did. We shuffled instead to exploring the

circulation of objects in the secondary goods market, and how its social life adds

values of other kinds besides just monetary.

This direction led us to a whole other area, far from

where we started, though on hindsight, not too far. I certainly had to learn

not to be too precious about ideas – that would not be productive otherwise.

Where we first began, we thought of different contexts outside of the museum.

Now we were jumping right back into the museum through the same pedestrian

objects that interested us in the beginning, along with most of the ideas we

explored in slightly new form. The conceptual landscape surrounding us was

quite familiar. On Sungei Road, we spoke about the negotiation of value and the

circulation of objects as goods. Yet, with the institution of the museum, it

negates most value systems, and through an acquisition, removes these

pedestrian objects from circulation to be held as inalienable.

Before setting out to type away at this essay, I was

feeling frustrated from all the meandering and ambiguity about where this

exhibition is going. But coming to this point, I realise that ambiguity gave

this collaboration with the other participants fluidity and flexibility. I

would like to think that all of us were free to travel in different directions

in the outer space of our minds, discuss those directions and converge together

again. This essay itself was an exercise in the journey out to space on my part,

but with an end point in sight, in an effort to make sense of where we were

before. It is riddled with my own subjectivity, and I would hazard a guess that

if other members of my group were to chart a conceptual topography of this

exhibition, it would be different.

I was especially frustrated because I had thought of

an exhibition as a text, written by an author. And I thought, “If an exhibition

is a text embedded with a message, then having multiple authors would dilute

that message”. And so I struggled with understanding what that message in our

exhibition is, thinking it was diluted. There are of course large bodies of

sources that debate this understanding of exhibition as text, with many

problematising and rejecting it, but I am ill equipped to enter that debate

now, at this point. I decided instead to revisit Clifford Geertz and his

interpretive anthropology. This might not be an original thought, but what if

we understood exhibitions to be symbolic gestures, like the Balinese cockfight?

An exhibition is a symbolic gesture, like a wink, but

on a larger scale. And curators are both performers of this gesture attempting

to convey meaning, but also self-reflexive interpreters attempting to understand the

context and giving a thick description of that gesture. In which case, collaboration

is about working out an interpretation, a process that would not be as clear-cut

as crafting a message, and would benefit from constant meandering.